“I am just not sure why I would participate again,” I overheard someone say in response to being asked to be a stakeholder at an upcoming town hall. “I keep doing these events and I do not feel like what I am saying is actually having an impact.” Those of us committed to behavioral health system transformation would do well to take these words to heart, and examine closely the motivations and methods by which we seek insights from the communities we seek to serve.

“Stakeholder engagement” is a buzzword right now. Everyone realizes its importance — but as the person above noted, it sometimes doesn’t seem to make a difference. Furthermore, even the term itself is increasingly considered problematic as it evokes a power imbalance through the historical exclusion of people most directly affected by the decisions made. Finally, stakeholders often participate for free, sharing the same story, the same suggestions, and the same feedback over and over. Agencies and organizations want people to “come to the table,” but what if there is a better way to invite the community to participate in the development, reform, or evaluation of a program or idea? What if, instead of asking people to come to our table, those of us in positions of leadership earned enough trust from communities to get an invitation to their tables?

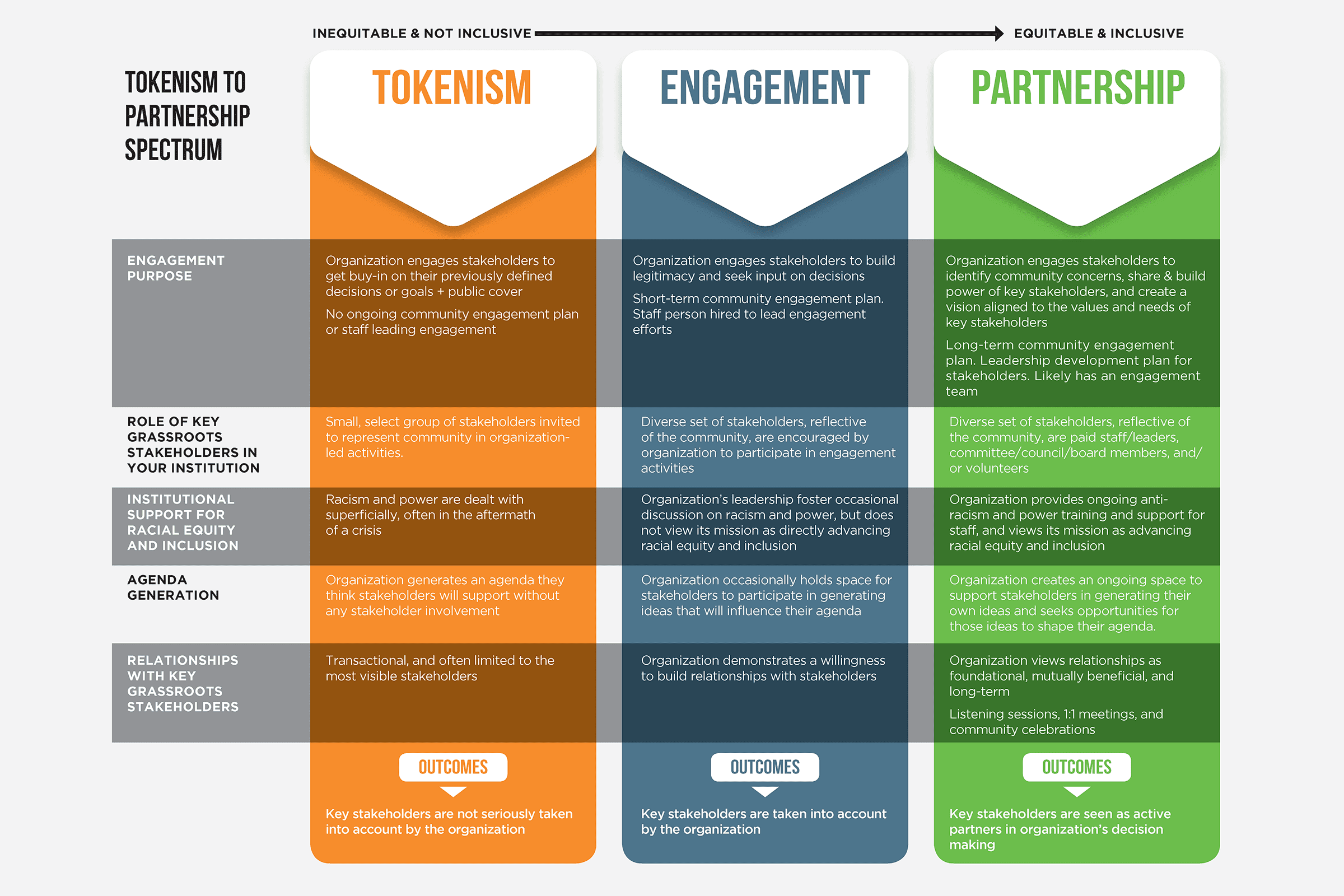

Historically marginalized groups like Black, Indigenous & People of Color (BIPOC), lesbian, gay, transgender, bisexual, queer, intersex, & asexual (LGBTQIA+) people, and people experiencing homelessness or serious mental illness tend to experience worse outcomes in behavioral health access and delivery — including involvement with the criminal justice system and higher rates of suicide, incarceration, and involuntary treatment. These groups are also less likely to be engaged in policy or program design or in community impact studies. After a long history of institutional trauma and tokenism, it is no wonder that mistrust sometimes greets an invite to “our table.” Given this reality, how can a time- and resource-strapped organization tasked with “stakeholder engagement” stop perpetuating the discouragement expressed in that opening quote?

From From Tokenism to Partnership by Charles McDonald.

Reframing “Stakeholder Engagement”

Typical stakeholder engagement tends to favor certain groups; lacks shared decision-making; perpetuates power imbalances; and takes a retrospective approach, i.e., including people only after much of the design or decision-making has already been completed. Community partnering, by contrast, happens at the community level and seeks to partner with individuals rather than simply take their knowledge or perpetuate tokenism. This approach involves people in decisions made about the programs or policies that directly affect them, and taps into the wisdom and strengths present at the local level. In Engaging Indigenous Community Partners in Hawaii, the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors declares that “Behavioral health officials must see culture as a cornerstone of resilience and wellbeing.” When organizations become able to elevate people with lived experience (PWLE) and members of the community to the status of expert, the work of dismantling power structures can begin, the information gleaned will be more authentic, and the resulting product will be more meaningful to both the organization and the community.

The Right Approach at the Right Stage

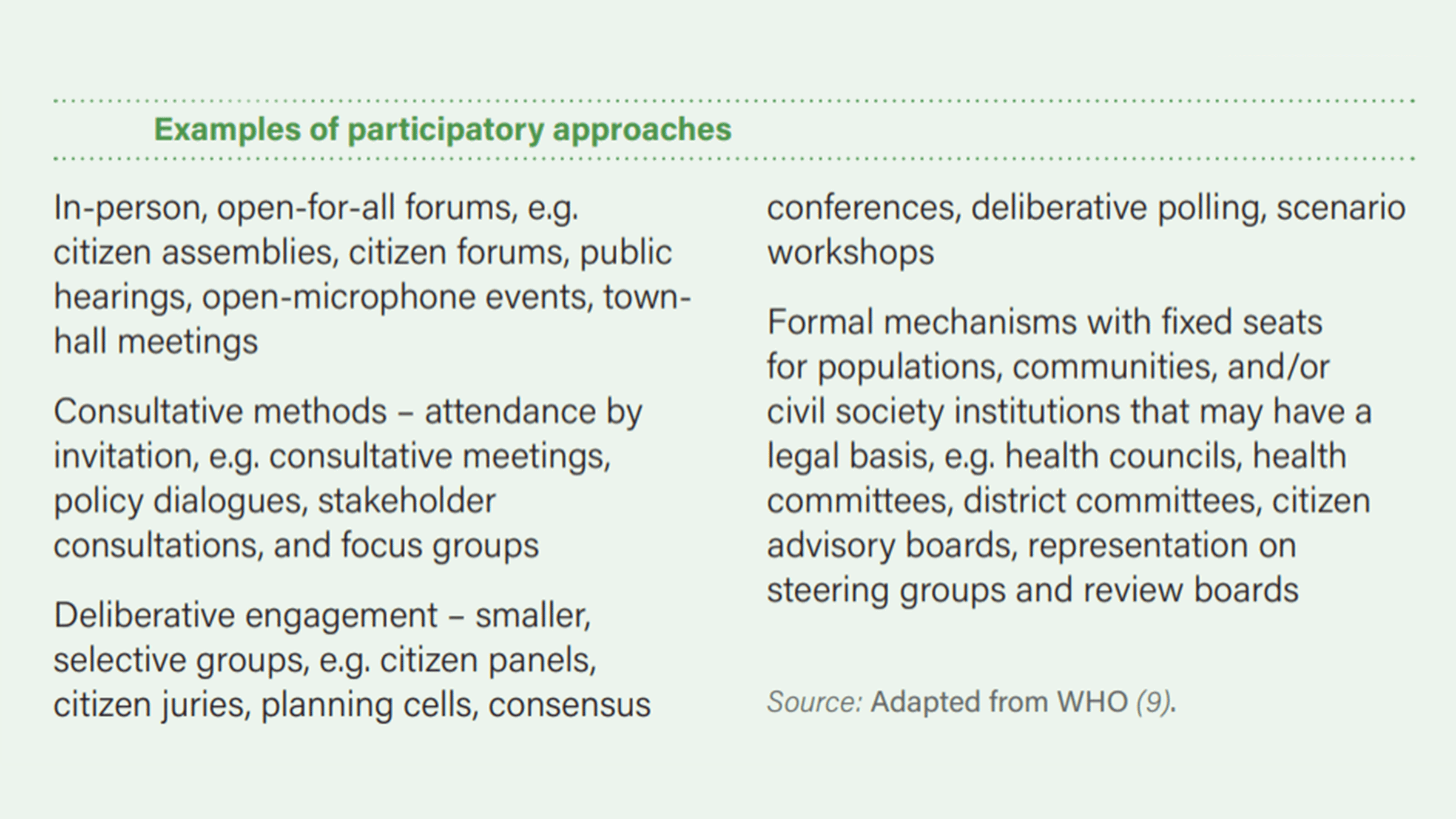

Is your organization trying to gather or share information, co-create a program or policy, or receive feedback on an existing program? Each of these goals is different, and refining your purpose can help guide the approach with which to engage individuals or groups.

In-person, open-for-all forums can be helpful when an organization is aiming to share or collect information and there is a reason for not engaging in a co-creation process. Such events can be used to collect broad feedback that can determine next steps.

Consultative methods can be utilized to gather targeted information for an organization to gain a deeper understanding of an issue or topic, or to learn from a specific set of people. These methods work well in the beginning of a development or reform process.

Deliberative engagement starts to utilize a co-creation ethos by relying on the expertise of a small group to influence policy or program development. Deliberative engagement can be used as an iterative tool throughout the process.

Formal mechanisms fully elevate the voice of PWLE and embrace both co-creation and shared decision-making throughout the process, helping organizations to both avoid tokenism and the solicitation of retroactive, meaningless feedback.

Trust Must Be Earned

Trust-building is a true iterative process that requires the commitment of both time and resources. To reach people who would not typically engage due to historical harm or tokenism, organizations should consider using targeted peer-to-peer outreach, establishing a presence in community organizations, and making offerings to promote reciprocity. Peer outreach can be useful if the organization has established trust with one person who is willing to be the spokesperson for the work and for engagement opportunities. Organizations should not underestimate the value of showing up in communities, as this can communicate that participation is considered truly necessary.

Make the Engagement Appealing, Equitable, and Worthwhile

To ensure that people are able to participate, organizations must strive toward equity from the invitation all the way to the initial engagement:

- Make participation attractive through a commitment to accountability and equal partnerships — and by compensating people for their lived expertise at a level commensurate with what is paid to consultants who bring other kinds of knowledge.

- Cover the costs of childcare and transportation.

- Explicitly commit to shared decision-making and not just information sharing or gathering.

- Provide background training to ensure that everyone adequately understands the issue and goals.

- Allow voting rights for all participants, not just a select few with organizational connections.

Meet the Needs of Participants

Consider the format and frequency of the sessions, and seek participatory approaches that suit the needs, expertise, desires, and resources of the communities being engaged. If a two-way discussion is required, consider a small group format. How comfortable are the participants with the use of video conferencing technology? While technology may be viewed as a convenient option, the commitment of travel can be a meaningful way to communicate to the community that it is valued.

Stay Accountable

Build specific strategies into your engagement plan to engage PWLE throughout the change-making process. These could include designating a board seat; involving PWLE in writing regulatory language and designing programs; inviting ongoing feedback or testimony to leaders; or involving PWLE in creating and reviewing promotional materials. For participants who do not stay involved throughout, make a plan for communicating back to them how their information was used. Perhaps their feedback improved programming, altered proposed regulatory language, helped the organization to reach more people, or created a culturally responsive intervention. Organizations can share such impacts through a reconvening, a newsletter, or a website update, with an emphasis on specifically how the participation of community partners helped influence the effort.

As behavioral health professionals, we have a profound responsibility to our communities to recognize the imbalance of power that permeates the history of behavioral health care design and delivery. By tapping into the expertise of people with lived experience, elders, community members, natural helpers, and other partners, we can reshape the ethos of behavioral health care from one of power imbalance and erasure of cultural identity, to one that celebrates the strengths, identities, and wisdom of the people and communities we serve.