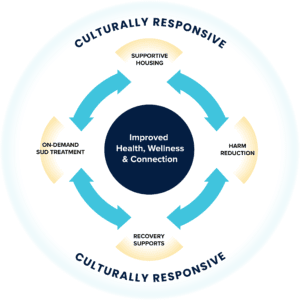

On any given day, news stories across the country highlight lives impacted by the addictions and overdose epidemic. Drug-related deaths have increased significantly since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and a recent study finds that since 2015, overdose deaths have risen fastest in Black, Hispanic, and Latino communities. One of the populations most affected by this crisis is people experiencing homelessness. The surge in fatalities related to fentanyl and chemically altered methamphetamine necessitates new engagement strategies in our efforts to end homelessness: Harm reduction is an effective strategy, but harm reduction alone is not enough. In order to reduce overdose deaths and improve the health and recovery of people with substance use disorders (SUDs), harm reduction must be combined with culturally responsive supportive housing, recovery supports, and on-demand treatment.

Combined Interventions Save Lives

The founding principles of harm reduction place people at the center of decision-making about their own substance use, reducing risk through education, resources that promote safe use, and opportunities to seek treatment and recovery when they desire. A non-judgmental and non-coercive approach to services, supportive of improved quality of community life and well-being, lays the groundwork for authentic engagement and inclusion in the services that people with SUDs choose to accept, and positions them as the primary agents in shaping SUD program design and policies. Harm reduction interventions must acknowledge the impact of poverty, class, racism, social isolation, trauma, sex-based discrimination, and other inequities in people’s vulnerability to drug-related harm. Rather than working solely to support reduced risk in substance use, harm reduction attempts to offer an entire continuum of supports that can help individuals move from active use to lower-risk use, abstinence, recovery, health, and wellness if and when they are ready.

It follows naturally that combining the harm reduction approach with culturally responsive supportive housing, SUD treatment access, and peer-delivered recovery supports can significantly improve how people with active SUDs envision a pathway to recovery, which may include abstinence. The potential of such a multifaceted response has yet to be fully realized, but many promising collaborations are beginning to change the story.

Recovery is Possible

The definition of recovery put forth by the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration (SAMHSA) describes a process of striving toward full potential. This process is based on ten guiding principles, the first of which is “hope.” Individuals immersed in the active disease of addiction are often overcome by feelings of helplessness and hopelessness that preclude them from envisioning a life of recovery. While harm reduction is essential in saving lives, incorporating hope for a better life that includes health, home, purpose, and community is essential to achieving recovery. This internalized construct can be nurtured through motivating messages that instill the belief that recovery is possible, that people with SUDs can and do get better, and that getting better may include attainment of educational goals; employment and economic self-sufficiency; housing stability; and reunification with family and friends.

Supportive Housing

SAMHSA recognizes housing as critical to recovery for individuals with SUDs who are experiencing homelessness. As outlined in a 2020 CMS Report to Congress, a growing body of research has documented that SUDs are strongly associated with homelessness. Affordable housing strategies for individuals with SUDs may vary depending on where a person is in their recovery. Those experiencing homelessness may need supportive housing, which combines affordable housing with intensive, voluntary services, and is one of the best-researched social determinants of health, with the literature documenting that evidence-based interventions directed at high-cost, high-need, low-income individuals improve health outcomes while decreasing emergency health care costs. The role of supportive housing — using both Housing First and recovery housing approaches — is vitally important to address the needs of people with SUDs and provide access to a range of health and behavioral health services and recovery supports.

Recovery Supports

As defined by SAMHSA, recovery supports services assist people in recovery and their families in these key ways:

- Foster health and resilience

- Increase housing to support recovery

- Reduce barriers to employment, education, and other life goals

- Secure necessary social supports in their chosen community

Recovery supports can be offered in alignment with culturally and linguistically appropriate services, and should address a full range of needs that facilitate recovery, wellness, and linkage to and coordination among health and behavioral health care providers, social service agencies, legal systems, and other community support systems.

Peer-delivered recovery supports align with SAMHSA’s guiding recovery principles. By sharing their own lived experience with SUDs, peers provide real-life demonstration of the benefits of recovery, and can relate to challenges and barriers facing those still struggling. In response to the opioid overdose epidemic, 53 states and territories report the use of peer recovery specialists as an evidence-based practice in outreach to people who use drugs. Peers work in settings as varied as homeless shelters, feeding centers, hospital emergency departments, detoxification centers, overdose hotspots, and correctional institutions, engaging individuals who were not necessarily looking for recovery and may not even have believed that recovery was possible. Incorporating peers into the service continuum of supportive housing strengthens the opportunity for long-term recovery. Upon engagement, peers can also provide vital connections to treatment and other recovery support services.

Treatment on Demand

Effective response to individuals living with SUDs requires that treatment be available on demand, whenever and wherever it is needed. Delays in treatment admission — due to lack of insurance coverage, capacity, or ineffective admission processes — result in lost opportunities. Some states have improved access by ensuring that SUD services are built into their 24/7 crisis stabilization centers. Published by the National Association of State Mental Health Program Directors, “Addressing Substance Use in Behavioral Health Crisis Care: A Companion Resource to the SAMHSA Crisis Toolkit” offers three examples of such centers functioning as entry points into SUD services. Supportive housing providers can help residents connect to SUD services by establishing relationships with community-based SUD providers, creating clear referral pathways, and providing training to staff — or, like the LaCHATS supportive housing program in Baton Rouge, LA, they can even embed evidence-based SUD treatment onsite. In some communities, treatment providers have established mobile programs at supportive housing sites to engage residents and offer a connection to treatment. The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration’s 2021 Final Rule approving the expansion of mobile units offering methadone treatment provides a new mechanism to reach, engage, and treat populations most at-risk, which could include individuals experiencing homelessness and those residing in supportive housing.

Cultural Responsiveness is Key

All of these interventions must be offered in a culturally responsive manner to address the substantial disparities that are documented in both substance abuse treatment and homelessness services. Members of racially marginalized groups are less likely than their white counterparts to engage in treatment, and when they do, are more likely to drop out before completion.

A culturally responsive system of supportive housing, harm reduction, peer supports, and on-demand treatment must:

- Recognize the impact that a long history of indigenous invisibility, anti-Blackness, and white supremacy culture has had on access to these systems; only a racial equity lens will help address the persistent drivers of inequity and SUD treatment disparities for each racially disenfranchised group.

- Engage communities of color with lived expertise of homelessness and SUD in the co-development and delivery of systems of care.

- Use an intersectional analysis to address the compounding impacts of multiple forms of oppression such as racism intersecting with ableism, cisgenderism, and heterosexism, to name a few.

- Identify a systems change approach that recognizes the role of systems in creating and perpetuating inequities.

- Lift up indigenous ways of healing, Black liberation theology, cultural assets, community knowledge, and resilience that are often devalued and pathologized.

- Make services welcoming, accessible, relevant, and trustworthy by ensuring competent language access and incorporating diverse cultural approaches, strengths, and perspectives from the communities served.

At the very heart of cultural responsiveness rests cultural humility, which is developed through self-reflection and centers the desire to fix power imbalances and develop partnerships with service recipients to advocate for systems change. Cultural humility requires members of the dominant white culture to engage with people from a space that mitigates hyper-professionalization, elitism, and white saviorism.

Combining Approaches for Success

The rate of deaths resulting from drug overdoses shows clearly that comprehensive interventions are required to save lives. An all-hands-on-deck approach is needed, bringing together and coordinating all of the evidence-based practices and principles described here in order to meet the needs of our most vulnerable community members: people experiencing homelessness and racially marginalized groups. Look for a TAC Issue Brief this summer on how communities can innovate to bring together culturally responsive supportive housing, harm reduction, recovery supports, and on-demand SUD treatment.